|

A soldier with a PackBot. When asked how science fiction writer Isaac Asimov might react to real-world warbots like these, iRobot’s co-founder and chairman Helen Greiner responds, “I think he would think it is cool as hell.” (Photograph courtesy of iRobot) |

A Predator drone is prepared for launch. The number of drones in the U.S. military went from only a handful in 2001 to some 5,300 in 2008. After 9/11, Pentagon buyers told one robotics executive, “Make ‘em as fast as you can.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

|

The Predator drone, which can stay in the air for twenty-four hours, is one of the most widely used and effective weapons in the force. “If you want to pull the trigger and take out bad guys, you fly a Predator,” tells one report. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

A special task force of drones armed with weapons such as these found and killed more than 2,400 Iraqi insurgents, in just one year (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

|

The Global Hawk spy drone can take off by itself, fly 3,000 miles, spend a day spying on an area the size of the state of Maine, fly back 3,000 miles, and then land itself. Some uncharitably say it looks like “a flying albino whale.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

In reachback operations, the drones over Iraq and Afghanistan are actually flown by pilots back in Nevada. As one described fighting from a cubicle, “It’s antiseptic. It’s not as potent an emotion as being on the battlefield.” Says another, “It’s like a video game. It can get a little bloodthirsty. But it’s fucking cool.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

|

While the pilots are no longer at risk, the experience of fighting from home bases, some 7,500 miles away, does bring new psychological twists to war. “You see Americans killed in front of your eyes and then have to go to a PTA meeting,” tells one pilot. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

Zero ground robots were used in the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Some twelve thousand were in service there by the end of 2008. As one officer put it, “The Army of the Grand Robotic is taking place.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

|

A MARCBOT on patrol with US troops in Iraq. A jury-rigged version of the tiny robot was actually the first ground robot draw blood on the battlefield. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

“Stanley,” the robotic car from Stanford University that won the DARPA Grand Challenge race. By turning the research into a competition and offering prize money, the Pentagon was able to entice scientists and college students who wouldn’t normally work on war technologies to help solve its battlefield problems. (Photo courtesy of Stanford University) |

|

|

Stanley won the robotic race by “learning” how to drive. Tells its designer, “We trained Stanley…. The relationship was teacher and apprentice, as opposed to computer and programmer.” (Photo courtesy of Stanford University) |

Nicknamed “R2-D2” by the troops, the Counter Rocket Artillery Mortar system uses an automated machine gun to shoot down incoming missiles and rockets, which humans would be too slow to react to. A new version will mount a laser. (Photograph courtesy of Raytheon) |

|

|

A TALON robot in action. These technologies “save lives,” says a former Pentagon official. But he also worries that “There will be more marketing of wars. More ‘shock and awe’ talk to defray discussion of the costs.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

Military researchers are trying to make robots easier to control by “playing to the soldiers’ preconceptions.” And with young soldiers today, that means video games. (Photograph courtesy of iRobot) |

|

|

Two young Army soldiers prepare to launch a Raven drone. According to one report, one of the unexpected results of the new technologies is a “military culture clash between teenaged video gamers and veteran flight jocks for control of the drones.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

An Army infantryman tosses a Raven drone into the air. The drone has proved so useful and popular in Iraq that its maker was approached by the Chinese military for a demonstration. Some forty countries now make military robots, meaning the revolution will not just be an American one. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

A Fire Scout helicopter drone fires a missile on a target below. “This new technology creates new pressure points for international law,” tells one human rights worker. “You will be trying to apply international law written for the Second World War to Star Trek technology.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

A Warrior robot uncovers a hidden roadside bomb. While robots are a revolutionary technology, war still remains messy and difficult, with an enemy already learning how to fight back. (Photograph courtesy of iRobot) |

|

A TALON robot picking up a potential explosive. Many believe that fighting insurgencies doesn’t involve technology, but there is actually a very sophisticated back and forth between the two sides. “They’re always trying to outsmart us, and we’re always trying to outsmart them,” tells one US soldier. (Photograph courtesy of Foster-Miller) |

A soldier works on a TALON robot in Iraq. While these robots save lives, they also might be sending out an unintended message to the other side. One news editor in he Muslim world commented how such technologies made Americans look like “cowards because they send out machines to fight us…. They don’t want to fight us like real men, but are afraid to fight. So, we just have to kill a few of their soldiers to defeat them.” (Photograph courtesy of Foster-Miller) |

|

SWORDS, made by Foster-Miller, is a robot armed with the user’s choice of weapons, ranging from machine guns to rockets. It gives new meaning to the term “killer app.” (Photograph courtesy of Foster-Miller) |

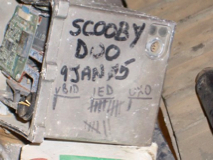

Scooby Doo, one of the very first robots “killed in action” in Iraq, blown up by an insurgent’s roadside bomb. It now rests in the offices of its manufacturer, iRobot. One commander put a positive spin on such losses, “When a robot dies, you don’t have to write a letter to its mother.” (Author photo) |

|

Scooby Doo’s human squadmates kept track of the number of dangerous missions the robot went out on, keeping them alive. When the robot could not be repaired, it left them very upset. He didn’t want a new robot but “wanted Scooby Doo back.” (Author photo) |

One concept of robotic warfare is the “warfighter’s associate” idea, where a mixed team of robots, such as PackBot here, and human soldiers would jointly carry out missions. (Photograph courtesy of iRobot) |

|

Sometimes, for all their sophistication, robots still need a little help from their friends. (Photograph courtesy of iRobot) |

Unmanned submarines are increasingly being used for the most dangerous roles under the water as well. This includes hunting for mines and patrolling waters close to shore, missions consider too risky to send in expensive nuclear-powered manned submarines. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

“In both war and police actions, you will see more and more of robots in all shapes and sizes…. There is a huge growth curve, with no signs of slowing down,” tells one analyst. “And that is before you get into the sexy, futuristic stuff.” (Author photo) |

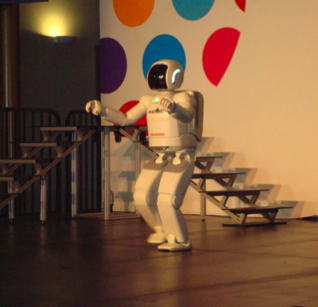

Asimo, a humanoid robot built by Honda. Standing just over four feet tall, this real world version of the Twiki robot from Buck Rodgers can run, jump, dance, recognize faces, and even hook up to the Internet. (Author photo) |

|

The Actroid is robot not only is incredibly lifelike, but also can understand forty thousand phrases in four languages and give answers to more than two thousand questions it might encounter. Owned by the same company behind Hello Kitty, its Web site also notes that “rentals are now available.” Such lifelike robots will open up new questions of ethics and rights. (Author photo) |

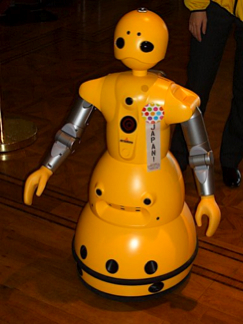

Wakamura is a cross between a house sitter and nanny robot, able to patrol the house, call the police or doctors in an emergency, and wake the family in the mornings and tell them about the weather and the news. In Japan, the little robot has also become a “companion” for elderly shut-ins. (Author photo). |

|

As part of its design, Wakamura can recognize faces, makes eye contact, and start conversations. But robots are notoriously tight-lipped during interviews. (Author photo) |

One concept being explored for twenty-first century war at sea is the idea of a mothership, where a warship would serve as the hub for a tiny fleet of unmanned drones and submarines. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

Described as looking like “a set piece from the television program Battlestar Galactica, the X-45 UCAV is designed to take on the most dangerous roles in the air and, perhaps, even replace manned fighter planes one day. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

One focus of Pentagon research is on bio-inspired robots, such as tiny insect-like robots that could fly up to windowsills and perch and stare inside or climb up walls or into pipes. Many worry about the end of privacy they portend. (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

|

The Crusher is a prototype of a next generation autonomous robotic fighting vehicle. The current robots at war are already outdated. The concern, as Isaac Asimov once said, is that “science gathers knowledge faster than society gathers wisdom.” (Photograph courtesy of the U.S. Department of Defense) |

The Robotics Revolution and Conflict in the 21st Century